Risk Alert 110: Work Safety - Adverse Weather

Introduction

The Club regularly experiences crew injury claims and. one source of these claims involves activities being undertaken during heavy weather.

This article will review some aspects of these risks.

Considerations

Masters and owners have an obligation to ensure ships’ staff are provided with a safe workplace and that they are regularly trained in emergency procedures.

Just as masters and owners have a duty of care to provide a safe workplace, crew members have a duty of care to ensure that they themselves work safely and are conscious of the safety of others.

While there is a significantly higher exposure to the environment when working on an open deck during adverse weather, there can also be significant risks present in what could be considered sheltered workspaces.

Activities may be urgently required to secure the safety of the vessel and its crew. Risks must always be properly identified, evaluated, and mitigated as far as reasonably practicable, particularly when working on and below deck in adverse weather. Risk assessments, procedures, toolbox talks and the appropriate permit to work are particularly important before commencing any task.

Contributory factors to heavy weather injury could include:

- Vessel motions - rogue waves varying in direction and size could induce a sudden and severe roll. Similarly, parametric rolling could result in a dangerous situation on board.

- Housekeeping issues – leaks, spills, litter, loose / unsecured floorplates, and other hazards such as unsecured doors, hatches or other accessways etc

- Tripping hazards (design / construction)

- Slippery decks (wet / icing / oily)

- Illumination, ventilation, and air quality

- Noise, vibrations, and other physical attributes

- Hot surfaces

- The need to lift/move heavy loads

- Condition of ladders, walkways, floorplates, railings, and their appendages such as safety riggings including lifelines, fall arrestors etc.

- Fatigue and mental occupational health

- Emergency situations

- Need for access to:

- Unmanned Machinery Spaces

- Cargo spaces

Appropriate PPE could help prevent a serious injury and improve the chances of survival and rescue if a person is washed overboard. In winter conditions the casualty would certainly be affected by cold water shock and hypothermia would soon set in, resulting potentially in unconsciousness and death. Wearing proper PPE such as an immersion suit and a lifejacket can significantly increase the seafarer’s chances of survival, and rescue.

Factors compromising survival in cold water:

- Human body cools 4 to 5 times faster in water than in air.

- Initial response upon immersion in cold water may include the inability to hold one’s breath, an involuntary gasp followed by uncontrollable breathing and an inevitable increase of stress on the heart. These responses normally last for about 3 minutes and are the body’s reaction to a sudden fall in skin temperature.

- Long-term immersion cools vital organs such as the heart and lungs to hypothermic levels, depending on factors such as wearing warm clothing.

- The survival time in sea water, at a temperature of 5 °C, wearing only working clothes, is predicted to be less than an hour.

Code of safe working practices for merchant seafarers (COSWP) 2024 addresses these risks in the Chapter 11 - Safe movement on board ship.

COSWP 2024 Ch11/11.11 Adverse Weather states:

11.11.1 When expecting adverse weather rig lifelines in appropriate locations on deck.

11.11.2 Nobody should be on deck in adverse weather unless it is necessary for the safety of the ship or life at sea. Where possible delay the work until conditions have improved; for example, until daylight or the next port of call.

11.11.3 Inspect the lashings of all deck cargo. Tighten them, as necessary, when rough weather is expected and check them periodically as conditions allow. Secure the anchors, and ft and seal the hawse and spurling pipe covers, regardless of the expected voyage duration. If ventilation to storerooms has temporarily been stopped during bad weather, seafarers should not enter until the enclosed space entry procedures have been completed (see section 15.1.7).

11.11.4 The master should authorise any work on deck during adverse weather and the bridge watch should be informed. Do a risk assessment, and complete a permit to work and a company checklist for work on deck in heavy weather.

11.11.5 Any seafarers who need to go on deck during adverse weather should wear a lifejacket suitable for working in, a safety harness (which can be attached to lifelines) and waterproof personal protective equipment (PPE) including full head protection. They should have a water-resistant UHF radio; also consider providing a head-mounted torch.

11.11.6 Seafarers should work in pairs or in teams and be supervised by a competent person .

11.11.7 Consider using stabilising fins (if fitted) to reduce rolling, and adjusting the vessel’s course and speed to mitigate the conditions on deck. If possible, visible communication should be maintained with the bridge; if not, use another continuous means of communication.

COSWP 2024 Ch11/ 11.11.8 draws attention to points that are often overlooked:

- Watch out for tripping hazards and protrusions such as pipes and framing.

- Be aware that the ship could roll suddenly or heavily at any time.

- It is dangerous to swing on or vault over stair rails, guardrails or pipes.

- Jumping off hatches can cause injuries.

- Keep manholes and other deck accesses closed when not in use; put up guardrails and post warning signs they are open.

- Clean up spillages (e.g., of oil, chemicals, grease, soapy water) as soon as practicable.

- Treat areas made slippery by snow, ice or water with sand or another suitable substance.

- Place warning signs to indicate where there are temporary obstacles.

- Clear up litter and loose objects such as tools.

- Coil wires and ropes and stow them away securely.

- Rig lifelines securely across open decks in rough weather.

- Stairways and ladders are usually at a steeper angle than is normal ashore.

- Always secure ladders and keep steps in good condition. Take care when using ladders and gangways providing access to or about the vessel, particularly when wearing gloves.

- Never obstruct the means of access to firefighting equipment, emergency escape routes and watertight doors.

- Take care while moving about the ship.

- Use appropriate equipment, PPE and clothing.

- Adapt to changes in sea conditions, procedures or equipment that could impact safe movement on the ship.

- Take particular care when working in dangerous areas, such as enclosed spaces or at height.

- Wear suitable footwear. This will protect toes against accidental stubbing and falling loads, give a good hold on deck and provide firm support while using ladders.

- Take extra care when using ladders wearing sea boots.

- Seafarers and other people on board must take care of their own health and safety when moving around the ship.

- Everyone must comply with any measures put in place for their safety.

- Do not operate watertight doors unless you are appropriately trained. Treat watertight doors as if they are in bridge operation mode at all times.

Case studies

The following extracts from flag state casualty investigation reports are intended to draw attention to and highlight interesting aspects of the hazards of working on board in heavy weather. It is not the Club’s intent to make any comment or judgement on the causation as may have been determined by investigators or on any presumption of liability.

Case 1 – Fall Overboard / Missing - Two Crew Members Overboard in cold North Atlantic waters.

02 January 2020, a bulk carrier in approximate location: 66° 05.0’ N 005° 26.3’ E, on passage from Murmansk, Russia towards Constanta, Romania with 37,668 metric tonnes of fertilizer and crew of 19.

Vessel was on reduced speed due to main engine issues. Wind Southwest at 44knots, estimated wave height recorded as 8m, visibility 5 nm, with both air and sea temperatures at 5 °C.

It was noticed that mooring ropes stored on the poop deck had moved, with some mooring ropes now hanging over the vessel’s guard rails.

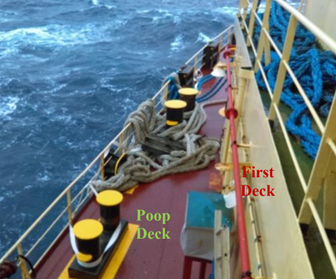

Starboard side, two ropes secured to poop deck railings the other end of one rope hauled onto the first deck - (Ref: TMSI Report: 01/2021)

In an endeavour to secure the mooring ropes two crew members (chief officer (C/O) and the deck trainee) were working on the poop deck and other crewmembers were handling the ropes on the first deck.

At one point, two large waves washed over the poop deck washing the C/O and deck trainee overboard.

Simulated crew positions at the time of the incident - (Ref: TMSI Report: 01/2021)

Master was informed, the wheel immediately ordered hard over, lookouts posted to keep sight of the MOB marker and the Coast guard notified. Due to the low speed and inclement weather conditions, it took over 20 minutes to turn on a reciprocal course and proceed towards the man overboard (MOB) position.

A search was carried out involving two Search & Rescue helicopters however, the operation was unsuccessful.

The safety investigation identified several inconsistencies in the operations on the poop deck.

Reportedly, during the securing operations, the C/O was heard telling the deck trainee that he needs to be secured with a rope. The C/O and trainee were both observed with ropes tied around their waists.

Once it was understood that the operation was now complete the C/O and deck trainee started making their way back from the poop deck. At this moment, a large wave is reported to have washed over the poop deck from the starboard to port side. Within seconds of the first a second, larger wave, then washed on board from the same direction. Soon after the second wave struck, several crew members noticed orange, winter jackets floating in the water at which time it became clear that both the C/O and the deck trainee had been washed overboard.

The investigation results appear to indicate:

- The C/O and deck trainee were not secured to the vessel.

- Immersion in, and exposure to cold water may have shortened the survival time of the C/O and deck trainee.

- A regular rope was used instead of a safety harness.

- The C/O and deck trainee released the line which they were using to secure themselves.

- Crew members not wearing lifejackets in adverse weather conditions while working on exposed deck.

- Identification of alternative stowage arrangement of mooring ropes was not considered safety critical.

- Securing method for mooring ropes did not suffice to prevent the ropes from scattering around the poop-deck and over the rails.

- Slow speed of the vessel due to main engine malfunction and adverse weather conditions severely hampered manoeuvrability.

Transport Malta Safety Investigation Report: 01/2021

Case 2 – 1 fatality and 3 crew members with serious injuries after large wave washed over forecastle.

07 October 2019, a Passenger / RORO vessel on a short coastal voyage from Cagliari, Sardegna to Porto Torres.

Vessel was experiencing North-westerly winds of Beaufort Force 8 and rough sea with a 5 m North-westerly swell. Air temperature 21 °C. Visibility 8nm.

Master altered the vessel’s course to about 335°, with the intention of reducing the rolling motions. The bosun reported to the bridge that the trestles and landing gear of two trailers on the forward-starboard side were damaged and that consequently, these trailers had collapsed.

Master instructed the chief officer (C/O) and the bosun to take some of the deck ratings and secure the damaged trailers with additional securing devices. The C/O and bosun established radio communication with the bridge before proceeding for the operations with four AB’s (AB1, AB2, AB3 & AB4) and an OS.

Vessels Route - (Ref: TMSI Report: 17/2020)

Damage to trailers behind deckhouse- (Ref: TMSI Report: 17/2020)

The four AB’s and the OS waited in a sheltered area under the ramp on the port side while the C/O and bosun went to inspect the damaged trestles and landing gears.

Whilst the C/O was surveying the area, he realised that the bosun was not around. The bosun apparently left the cargo bay suddenly to inspect the anchor lashings on the forecastle deck forward of the deckhouse (that also acts as a wave breaker) without informing C/O.

fDeck 4 - (Ref: TMSI Report: 17/2020)

Looking aft - Forecastle deck / Deck house acting as wave breaker - (Ref: TMSI Report: 17/2020)

While on the forecastle deck the bosun noted that the anchor lashings were loose (they were not secured in compliance with the company’s procedures) and started walking back towards the ramp to call for assistance. At around this time a large wave washed over the vessels bow.

The bosun fell on deck but managed to get up and call for assistance to secure the anchors. AB1, AB2 & AB3 responded to the bosun and proceeded to the forecastle while AB4 and the OS remained in the sheltered area. Another wave washed over the vessel’s bow and this time struck all four crew members, pushing them violently against the various structures and fittings on the forecastle deck.

After some time, the C/O reached the forecastle and found all three ABs lying on the forecastle deck. The bosun was nowhere in sight. AB3 called out to the C/O for help as his legs were injured. The C/O helped AB3 to a safer location and then went to check on the others.

The C/O found AB1 lying face down and unresponsive between the two windlasses. He checked for vital signs and, on not noticing any, called for AB4. The C/O and AB4 carried AB1 towards the accommodation entrance. C/O then noticed that the bosun and the other two ABs had managed to walk back.

The bosun and two Abs (AB 2 and AB3) suffered serious injuries, while AB1 suffered fatal injuries, because of this occurrence. The autopsy conducted on AB1 revealed a broken neck, fractures in the left ribs, a fracture of the left humerus, and internal bleeding in the thoracic and abdominal regions. The broken neck was stated to have played an important role in the fatality of the AB, as this injury, by itself, would be severe enough to cause death within a very short span of time.

In addition to the fatality and the injuries suffered by the ship’s crew there was structural damage to the vessel, damage to cargo securing equipment and damage to the cargo trailers.

Area (Red circle) where AB1 was found (Ref: TMSI Report: 17/2020))

The investigation results appear to indicate:

- The alteration of course to reduce the rolling motions to facilitate the operations to secure lashings on deck resulted in winds closer to vessels stem and waves washing on forecastle deck.

- There appeared to be an acceptance of risk of injury in the crew members mind, which appeared to outweigh the perceived risk of anchors not being secured at that time. Bosun had fallen on the forecastle deck before he called for other crew members without taking the Master and C/O into confidence of his intent.

- Anchors were not secured upon departure port contrary to the two heavy weather checklists completed prior to the accident.

- Securing of the anchors for such voyages was not common practice on board the vessel.

- The vessel was inherently ‘tender’ and susceptible to water being shipped onto her deck.

- The motions of the vessel in heavy weather conditions, shifting of the cargo within the trailers due to the same and the subsequent strain on the cargo securing devices, along with the probability of an overweight trailer, was likely to have resulted in the failure of some trailer supports which, in turn, led to further cargo shifting and subsequent damages to some trailers.

- While the rest hours records appeared to be in order the investigation was unable to establish the impact of heavy weather on the quality of their rest.

Transport Malta Safety Investigation Report: 17/2020

Case 3 – Fatal Slip / Crushed in Engine Room

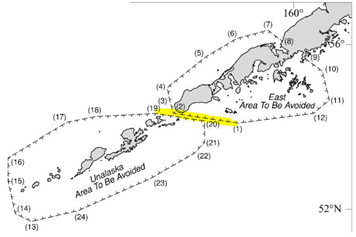

08 October 2018, a container vessel was on a short voyage from Kodiak, Alaska to Dutch Harbor, Alaska, manned by 23 crew members.

On 08 October, heavy weather was experienced by the vessel, noticed to intensify throughout the day. South-Easterly winds Beaufort Force (BF) 6 at 0400 (LT), subsequently reached BF 9 at noon. Air temperature was 10 °C. Atmospheric pressure had dropped steadily, from 1008 mb at midnight to 1000 mb at 0900 (LT).

At around 0900 (LT), a heavy weather checklist was filled, and all works were suspended.

By noon, the wind was blowing steadily from Southeast and had reached BF 9. The vessel was on a course of 278° (T), with sea and swell from her port quarter, causing her to roll 30° to 35°.

Vessel rolling heavily to starboard – photo from bridge dome camera – (Ref TMSI Report: 18/2019)

Unimak Pass’s safety fairway (in yellow) – (Ref TMSI Report: 18/2019)

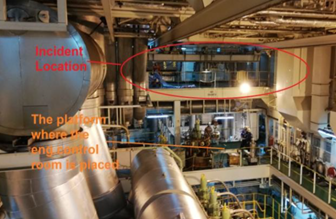

At 1225, as the vessel commenced her passage through the Unimak Pass, the second engineer (2/E), who was on duty, heard a very loud noise coming from the engine-room. Upon inspection, 2/E found that a spare auxiliary blower, amongst other items, had broken from its lashing and was moving freely on deck.

Platform where blowers were stowed (red) – (Ref TMSI Report: 18/2019)

At 1235 following discussion, the master and several of the ships staff proceeded to the engine-room. It was discovered that the free, spare auxiliary blower had ruptured the stern-tube gravity tank, from where oil had spilled making the deck slippery. Furthermore, it was noticed that several items had also broken loose from their securing arrangements and were moving freely around the deck creating obstacles for the crew.

The C/E ordered the engine-room crew to move out of the danger area and the master started to make his way to the bridge. The rolling motion now caused the blowers to move across the deck and towards the engine-room crew.

Both the fitter and the oiler slipped while trying to leave the area, the oiler being pulled clear by the 2/E who also slipped in the process.

The reefer technician pulled both, the 2/E and the oiler, to safety, however, the fitter, who was furthest from anyone’s reach, was crushed between the bulkhead and one of the blowers. As a result of being crushed the fitter sustained multiple injuries and succumbed to his injuries.

Lashed spare auxiliary blowers in the engine-room TMSI Report: 18/2019

The investigation results appear to indicate:

- Immediate cause of the accident was failure of the lashings securing spare equipment.

- Weather reports received did not give cues of the inclement weather developing in the vessels path.

- Having identified the developing situation the master ordered all works suspended and that heavy weather precautions be taken.

- Dunnage was not placed below the blowers to prevent them from sliding.

- The vessel suffered excessive angular velocity due to a high GM, causing violent rolling motions and excessive acceleration stresses on lashings.

- Stability of the vessel could not be further improved.

- SMS did not seem to address the engine-room space and the need to recheck and/or re-tighten items that were already lashed.

- Safe Working Loads of the lashings were not known and possibly not appropriate for securing the blowers.

- Vessel exposed to stern quartering seas and violent motions quickly developed being indicative that the vessel might have experienced parametric rolling.

- The crew appear to have acted in the belief that it was important to intervene as quickly as possible for fear that the moving blowers could fall onto the decks below, causing further damage.

- Alteration of course not an available option, this would have placed the vessel closer to danger of grounding and could have resulted in even more violent motions.

- Shelter as an option would only have been available about three to four hours after the accident

Transport Malta Safety Investigation Report: 18/2019

Case 4 – Fatal fall from accommodation internal stairway

22 November 2019, a bulk carrier on a voyage from Rouen, France, to Cienfuegos, Cuba.

Figure 1: MV Alma (Ref: TMSI Report: 22/2020)

Vessel was experiencing 25-knot winds from the North. Rough seas north-westerly swell of 3.5 m. Air and sea temperatures of 8 °C and 12 °C respectively. The vessel was rolling and pitching moderately.

At around 1953hours, on his way to the bridge, the third officer (3/O) met the electrical engineer (EE) in the stairway landing of deck ‘A’, wearing overalls and safety shoes. At about 1955 hours, the bosun, in his cabin on deck ‘A’, heard a sound from the accommodation stairway. On checking, he found the EE on his back at the bottom of the stairway.

As the EE appeared to be unconscious the bosun immediately called the bridge. The Master and C/O made their way to the area. and found the EE unconscious and breathing heavily, with no apparent external injuries. The crew placed a pillow under the EE’s head and covered him with a blanket. His vital signs appeared stable.

Stairway (Ref: TMSI Report: 22/2020)

The vessel diverted course towards the nearest port of Brest, France and the Company contacted for medical assistance. Crew members were assigned to monitor the condition of the injured EE.

At around 2230hours, the EE’s condition was reported as deteriorating and at approximately 2300hours the vessel was informed that helicopter evacuation was being arranged.

On 23 November, at about 0120hours, the EE’s breathing became shallower and stopped about five minutes later. No pulse could be detected, and Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was commenced. CPR was eventually stopped after confirmation that the crew member remained unresponsive.

The investigation results appear to indicate:

- The stairway was fitted with a handrail, its risers were evenly spaced, and it was reportedly well lit and free of defects and slippery substances.

- Shoes worn by the EE were in good condition, with the treads free of wear.

- Records of hours of work/rest did not indicate any excess of limits prescribed by MLC 2006.

- Death was caused by a severe head trauma.

The safety investigation hypothesized:

- In the absence of witnesses, it was not possible to determine why the EE was using the stairway.

- The EE either lost his footing or balance due to the rolling and pitching motions of the vessel, and subsequently fell down the stairway.

- The EE may not have been holding the handrail while descending the stairway.

Transport Malta Safety Investigation Report: 22/2020

Other Notable Cases:

Passenger vessel – 28 Sep 2000 - 570 miles west-south-west of Cork, Eire (Wave damage - Injuries / Damage to property)

On 28 September 2000, the vessel (on passage from New York to Southampton at 19.5 knots) was struck by a large wave amidships on her port side. 3 cabin windows on deck 5, and 3 cabin windows on deck 6 were breached, injuring the occupants, and causing extensive damage to the cabins and fittings. Storm covers had been fitted to the damaged windows on deck 5 but these were also breached.

One crew and six passengers suffered cuts and bruises; some passengers suffered from shock.

Passenger vessel – 30 July 2008 - 200 miles NNE North Cape, New Zealand (Gale force winds - Injuries / Damage to property)

During the evening of 30 July 2008, a cruise ship rolled heavily in gale force winds and high seas while returning to Auckland from an 8-day cruise of the South Pacific. Of the 1730 passengers and 671 crew on board, 77 were injured, with seven sustaining major injuries.

Many of the injuries sustained by the passengers and crew were caused by falls and contact with unsecured furnishings and loose objects in the busy public rooms, including rooms designated as passenger emergency muster stations.

Trawler – 18 April 2016 – 30nm NW of Orkney Islands (Cold water immersion – MOB / Fatality)

A crewman fell overboard from the stern of a 23.95m fishing vessel while the nets were being hauled. The weather was rough, and the crewman was not wearing a personal flotation device. The crewman managed to grab hold of the trawl warps and the crew hauled in the gear to pull him back towards the stern where he held onto a lifebuoy that had been lowered down to him.

The crew attempted to recover him from the water, but he appeared to let go of the lifebuoy, disappearing below the surface.

The crewman had been in the water, which was 9°C, for about 7 minutes. An extensive search was carried out by coastguard helicopters, military aircraft, and the fishing vessel’s crew, but without success. The crewman’s body was recovered by another fishing vessel nearly 4 months later.

Observations and Recommendations:

The above case studies highlight the need to understand and appreciate the hazards and risks associated with rough weather and the work environment, including the dynamics and nature of a vessel’s movements.

Good seamanship practices such as applying adequate lashings for all unsecured objects such as cargo, stores, spare gear, fixtures and fitting etc prior to setting sail could prevent a dangerous situation developing and the possibility of accidental injuries or worse. If for any reason, despite the forecast of adverse weather, a vessel intends to remain alongside a berth or at an anchorage, it is important to secure all loose objects and take other appropriate precautions such as the running of additional moorings, securing tug support, paying out additional anchor chain etc).

Weather routeing services and software are readily available to mariners, in addition to utilising the weather measurement and observation instruments available on board. While an advance indication of expected weather is usually available, it is essential that any sudden and unexpected change of weather conditions be duly reported to the Master in a timely manner.

Guidance on securing practices within the Code of Safe Practice for Cargo Stowage and Securing (CSS code), can be applied to all manner of large objects usually found on board a vessel. Other preparations for heavy weather such as the rigging of safety lines and heavy weather railings should also be implemented well in advance of any adverse weather.

The significance and importance of utilising the correct PPE appropriate to the conditions and activity, and in the correct manner, should be properly understood and appreciated by all.

Activities to be undertaken during adverse weather require risk assessing and appropriate planning in order to minimise and mitigate against the impact of the weather. Reducing the motions of the vessel or minimise exposure of the crew to the weather conditions if possible, such as changing course or speed, altering stability condition of the vessel and other appropriate measures appropriate to the situation should all be considered in order to minimise risk to the crew and vessel.

Work activities and movements should be planned, approved by a responsible person and authorised by the Master. Work should be constantly monitored, particularly those requiring access to any unmanned spaces or exposed locations, such as the weather decks, and the bridge watch must be informed. A permit to work and company checklist for working on deck in heavy weather must be completed.

Communication channels should be well established, agreed, understood and effective. Where possible, a buddy system should be implemented along with routine status reports to a continuously manned operations centre (Bridge, ECR, etc) that could quickly coordinate a response or assistance if required.

Any injuries, especially when at sea, should be treated having due care to the immediate surroundings in order to protect both the injured party and those responding, with due consideration to properly assessing the injury before taking the appropriate corrective action. Radio medical advice should be sought if necessary.

Fatigue, stress and mental health are frequently being identified as contributory causes of maritime casualties and incidents.

Some effective measures to help manage rest hours and avoid fatigue include ensuring manning levels are appropriate to the operational and trading requirements of the vessel. Ship staff exercising self-discipline and following basic professional courtesies, maintaining punctual time keeping at the change of watch.

Situational awareness is key, and it is important to remember that the sea is very dynamic and unpredictable in nature. A sudden freak wave for instance could suddenly throw one off balance (Physical senses could be dulled by the tedious rhythm of the vessels motion and vibrations making the seafarer oblivious to the changes).

Remember the old adage:

“One hand for me and one for the ship”

To summarise, key areas where consideration should be given when addressing the risks include:

- Dynamic nature of the environment

- Weather Routeing

- Course & speed appropriate to environmental conditions – reduce exposure & effects.

- Advance preparations for adverse weather

- Good seamanship practices & securing for sea

- Proper Planning of activities

- Good communication, maintain visual contact.

- Adequate illumination

- Appropriate PPE & equipment

- Safety lines rigged

- Working in Teams / pairs (buddy system)

- Fitness to work & adequate rest.

- Situational awareness & Safe conduct on board

- Necessity of the work – is it safety critical.

For the continuity and safe execution of the voyage essential activities may need to be performed, even in adverse weather, and these should be properly planned to have due consideration to the need for undertaking the activity, weighed against the overall safety of the crew, vessel, environment, and the cargo. Where necessary, these activities should be undertaken having due regard of all the circumstances, with appropriate consideration to the fact that the conditions or the situation could change suddenly and without warning. Risks need to be identified, assessed, and mitigated and the situation monitored constantly in accordance with the dynamics of the situation.

Always Plan For, and Expect, The Unexpected!!

Supportive Information

For further information on this or other Loss Prevention topics please contact the Loss Prevention Department, Steamship Insurance Management Services Ltd.

Tel: +44 20 7247 5490 Email:[email protected]